August likes the museum, but her auntie is sickened by the tokenism. One of the novel’s many powerful scenes finds August and her Aunt Missy rushing through the Historic Museum of Australia, searching for the cultural objects that might prove their Native Title Claim in time to stop the bulldozers. The mine is just the latest in a long list of expropriations that includes Land, Culture, and Children. It’s hard not to see this scenario as the emblematic Australian story. There’s tin under the ground and the impoverished town has rolled out the red carpet for a giant mining corporation. His granddaughter, August, returns home from England for his burial to find her grandmother in the process of being evicted. It is Albert’s death at the start of the book that sets the story in motion. In his old age, he began compiling an eccentric English–Wiradjuri dictionary, in which he tells of yura – wheat bunhaan – ashes ngiyawaygunhanha – always be and Biyaami – the spirit who ‘came upon the earth and decided to make it a beautiful place to live.’ It was once forbidden to speak Wiradjuri and the fact that any of these words exist at all is the central miracle of the novel. They taught him the old ways: ancient farming practices, dances, stories, language. With them he did things humans could not do. He learnt to like the Bible, but he was also a visionary, in league with the ancestors.

‘Can you hear it now?’Albert asks, ‘Say it – Ngu-ram-bang!’Īlbert Gondiwini was raised in an Aboriginal Boys Home, cut off from his people and his culture.

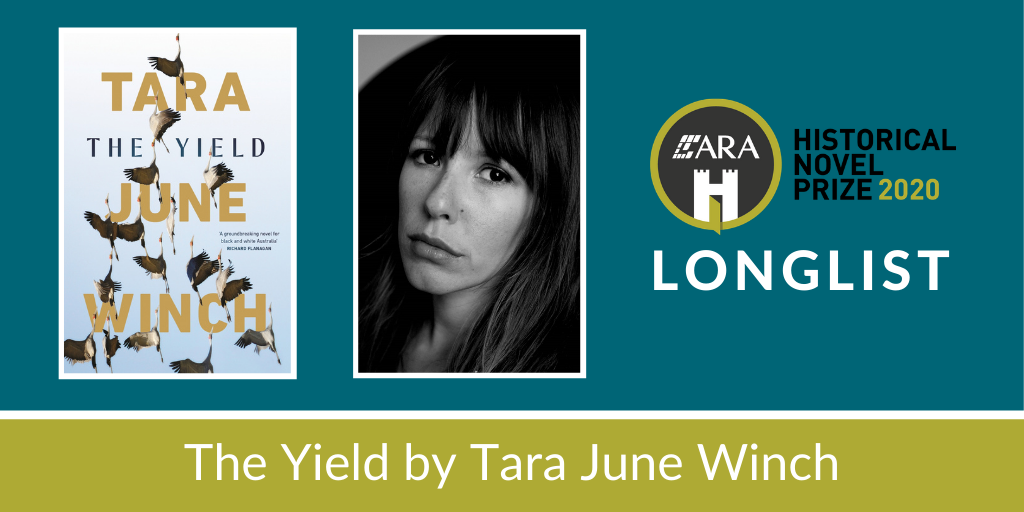

In Wiradjuri, a language once thought extinct, that word is Ngurambang. The Yield, Tara June Winch’s inspired second novel, begins and ends with an injunction: ‘Every person around should learn the word for country in the old language’ Albert Gondiwindi says.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)